VOICES OF CHANGE

Interviews with Monterey County Activists and Organizers, 1934-2015

Gary Karnes with Karen Araujo and Juan Martinez of The People’s Oral History Project

Voices of Change flier

This incredible project includes interviews with dozens of activists over the last forty years in Monterey County, California. This unique area, just 2 hours south of San Francisco was the place where many national and international social justices issues were confronted. Depressed wages and unsuitable working conditions were confronted by the United Farmworkers; environmental degradation and education is engaged by the Monterey Aquarium, one of the finest in the world. Women’s participation in public life is celebrated and encouraged. Even though Rosemary and Howard had both died before this book was compiled and published, their words are included.

Liz Fisher’s introduction to quotes from Rosemary and Howard included in Voices of Change:

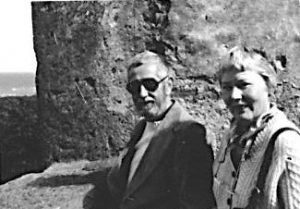

Rosemary Matson died on September 27, 2014. She had an initial interviewed by Karen and Gary just two months before she passed. There was not time to complete the interview before she passed. Being a colleague and longtime friend of Rosemary and Howard Matson (who died on August 17, 1993), I was able to fill in the details included here. I knew the Matson’s since 1982 and participated with Rosemary in many activities related to Women and Religion within the Unitarian Universalist Denomination.

Rosemary kept copies of publications she and Howard authored, and meticulous files chronicling their activist activities as well as those of their interesting colleagues and friends. Over the last eight years of her life, we reviewed together her extensive files on social change activities, articles about them individually and as a couple, and Howard’s sermons and manuscripts, both published and unpublished. During these years, my husband Bob Fisher and I produced several publications about the Matson’s activities based on these materials and our conversations.

Two years before she died, Rosemary entrusted important personal documents and files to me with the understanding that I would continue to further share this material with others who would benefit from knowing about she and Howard’s lives and activities. She believed that sharing the details of her and Howard’s activism, as well as that of others, helped people to understand the inequities of varied social situations and often inspired them to act on behalf of peace and justice issues. I agree. As you can tell, she loved this project and was proud that she and Howard are included. Can’t you see them both smiling?

Rosemary Matson in her own words:

In 1962, Howard received a call to become a minister in the Unitarian Church in San Francisco where one of his responsibilities was to provide leadership on social justice concerns. I began working for the Starr King School for the Ministry raising funds. I also worked for the Pacific Central District as the first woman ministerial settlement representative in the UUA. Thus began a very active and productive time for both Howard and me. It was the 1960s, remember.

In my 50s I hit my stride, channeling my energies and skills into working for women’s rights, women’s values, herstory, and looking at the influence that religion had on the status of women. In my 60s I discovered feminism and struggled to understand the difference between women’s rights and feminism.

In 1963 Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique was published. That book changed many lives, ours included. I joined the National Organization for Women (NOW) and subscribed to the new MS magazine. Women’s rights and women’s issues took over my life.

When I worked at Starr King school the students were all-male and the faculty was all-male. The curriculum was male–centered. My consciousness began to change in the early 70s as I worked for changes at the school. In 1971, four women applied to Starr King and were admitted. Prior to that date, there had only been two women in the school in the 1960s.

As part of my placement duties, I began to advocate to congregations that they consider women candidates. I also began revising the school’s promotional materials to be more gender inclusive. I demanded, along with several Board members, their own first names be used in the school catalog (i.e. Rosemary Matson, rather than Mrs. Howard Matson) causing quite a controversy. I also helped raise funds to endow a faculty position to be filled by a woman, another first.

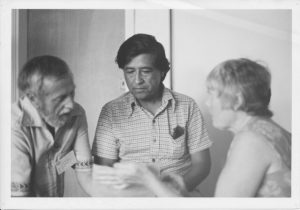

Howard Matson, Cesar Chavez, and Rosemary Matson

Howard Matson in his own words:

From 1971-78 I have been Minister for Migrant Farm Workers for the Unitarian Universalist Association. The UU Migrant Ministry partnered with the interfaith National Farmworker Ministry in various initiatives designed to complement the efforts of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers union that was trying to organize California’s fieldworkers. This included Methodists, Roman Catholics, Jews and Presbyterians among others. We joined striking workers on the picket line, urged supermarket shoppers to boycott non-–union produce and helped facilitate teach–ins. I often spoke about the farmworker struggle to UU audiences, and about Chavez’s non-violent, quasi–religious approach to worker mobilization.

I was in the hurly burly of things including those dangerous confrontations between Teamsters and the United Farm Workers. The clergy were present to help cool the violence. It was difficult to cool ourselves in the 120 degree heat of the Coachella Valley.

In the years I was minister for migrant farm workers it was clear to me the mere presence of a caring person in a crisis situation is the most important contribution one could make. Migrants are so alone as they wander from field to field in search of work. Even when families are together it is a lonely life. To live in a labor camp and to work fields close to where people live in real houses is a depressing experience.

Cesar Chavez remarks at the memorial service for Rufino Contreras who was murdered near El Centro, California on February 10th began — “It was a day without hope. It was a day without joy. The sun didn’t sing. The rain didn’t fall. Why was this such a day of evil? Because on this day, greed and injustice struck down our brother Rufino Contreras.” Near the end of his eulogy Cesar added — “If Rufino were alive today, what would he tell us? He would tell us don’t be afraid. Don’t be discouraged. He would tell us don’t cry for me, organize!”